History of Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery

Introduction

An old cemetery sits off Fourth Street in Athens, Georgia. Barely visible amidst lush underbrush, the occasional tilted tombstone or bent placard marks the final resting place of some of the town’s most eminent African Americans. Surrounded by a chain-link fence, the Morton plot occupies prime real estate near the front of the cemetery. Monroe Bowers “Pink” Morton was born a slave in 1856, but rose to become a wealthy Athenian, a successful builder, and the owner of the Morton Theatre. He, along with his mother, his first wife, his second wife, and his four children are buried near a large, granite tombstone. [1] Other graves are tucked away in the cemetery’s far reaches and back corners, but the names and messages are no less meaningful. “Sweet be thy rest till he bids thee arise,” reads the tombstone of John Nesbitt. A little lamb, carved in white stone, sit atop the grave of Addie May Davis, a seven-month old infant who died in 1907. [2] An intricately carved dove, open gate, and three chain links—symbolic of the Odd Fellows—features prominently on the tombstone of Anderson Matthews. So, too, does the message: “Sleep on dear husband and take thy rest / I loved you but God loved you best.” [3] Susie Horton and her two infant daughters, Emily and Mary, share a small granite marker, lying low among the tall grass.

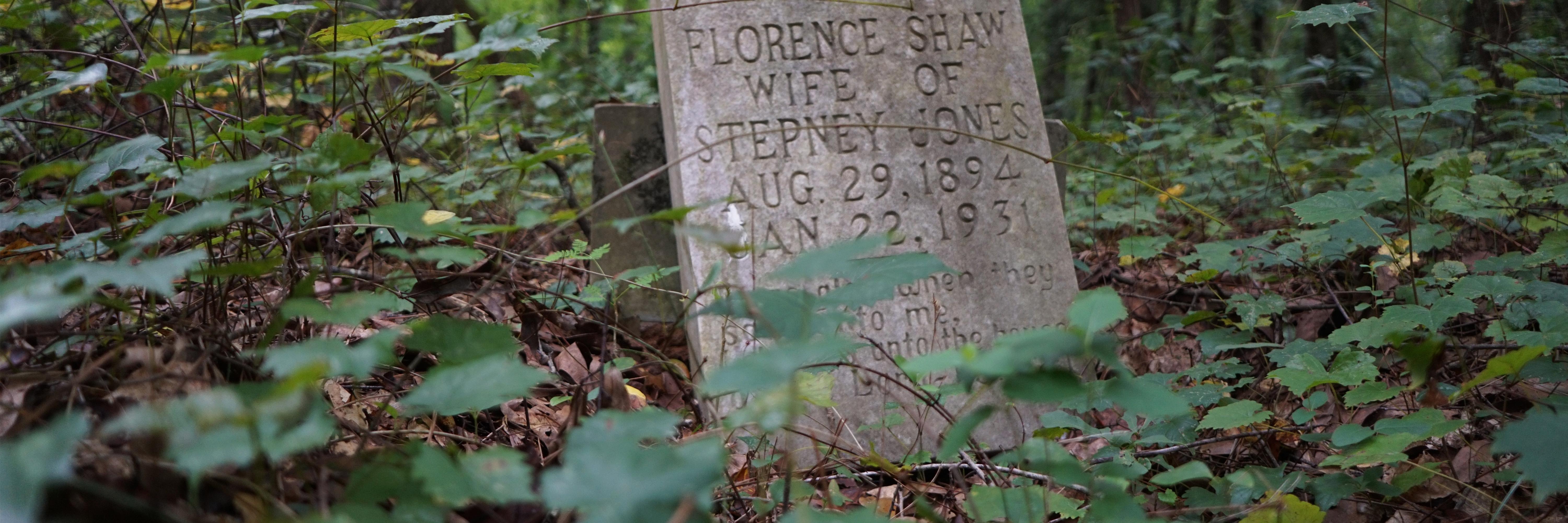

They are the lucky few. Their names and locations are known. They will, we hope, forever, have their name emblazoned above an eight by two-and-a-half foot plot of land in East Athens. Only 1,339 of the approximately 3,500 individuals buried at Gospel Pilgrim have some form of grave maker. Only 500 of the approximately 3,500 individuals have a known name, at all. Most are simply “unknown;” their identities and locations are lost to time. [4]

Families did not intentionally bury their loved ones in unmarked gravesites. Lacking financial means, some black families could not afford a stone marker; some planned to erect one later, but that time, more often than not, never came. Instead, these families marked gravesites as best they could—they showed their children, they planted flowers or trees, they marked the graves with household items. Carolyn Barnes’s grandfather “would point out where certain family members were buried and this was his way of sharing our family history. I remembered that in our family babies were buried at the foot of trees. So the rock at the bottom of trees in our family plots are not just rocks. Somebody, a baby is buried there. I am not sure if this was practiced by everybody in the community. But we did it,” recalled a resident of Washington, Georgia. [5]

Harking back to African tradition, it was customary to place decorative trinkets or other symbolic objects atop a grave. [6] Near the cemetery’s front gate, felt stars are nailed into a pine tree—perhaps indicating the final resting place of a mother, father, or child. [7] While many miles inland, shell and coral are common sights in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. Two conch shells, well-worn from exposure to the weather, grace the fence surrounding a gravesite. [8] According to popular belief “seashells served as a reminder that the deceased had gone to the watery world of the ancestors and their reflective properties protected the deceased from haints or bad spirits.” [9] Or it may have represented “an image of a river bottom, the environment in African belief under which the realm of the dead is located.” [10]

The flora and fauna, too, assumes meaning and purpose in African-American cemeteries. Yucca and prickly pear, for instance, keep spirits at bay. Oak and pine symbolize eternity. And, the weeping willow represents grief. [11]

Most plants in Gospel Pilgrim, however, don’t hold such symbolism. Wisteria strangles the dead. Its emerald vines choke the fieldstone, marble, and granite tombstones. Its leafy cover blankets unmarked, sunken graves—obscuring them from the view of a well-meaning passerby or a curious descendant. [12]

The end result is eerie: tilted gravestones emerge as haunted specters from the morning fog, broken shells perch, bird-like, atop granite walls, and the green vines consume it all. William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses describes the scene most accurately: “the grave, save for its rawness resembled any other marked off without order about the barren plot by shards of pottery and broken bottles and old brick and other objects insignificant to sight but actually of profound meaning and fatal to the touch which no white man could have read.”

In 2002, a title deed investigation of Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery determined that ownership of the land could not be traced to any living individual or operational organization. [14] Georgia law, however, “allows local governments to use local funds to care for" such property "without the local government assuming ownership or responsibility.” [15]

History

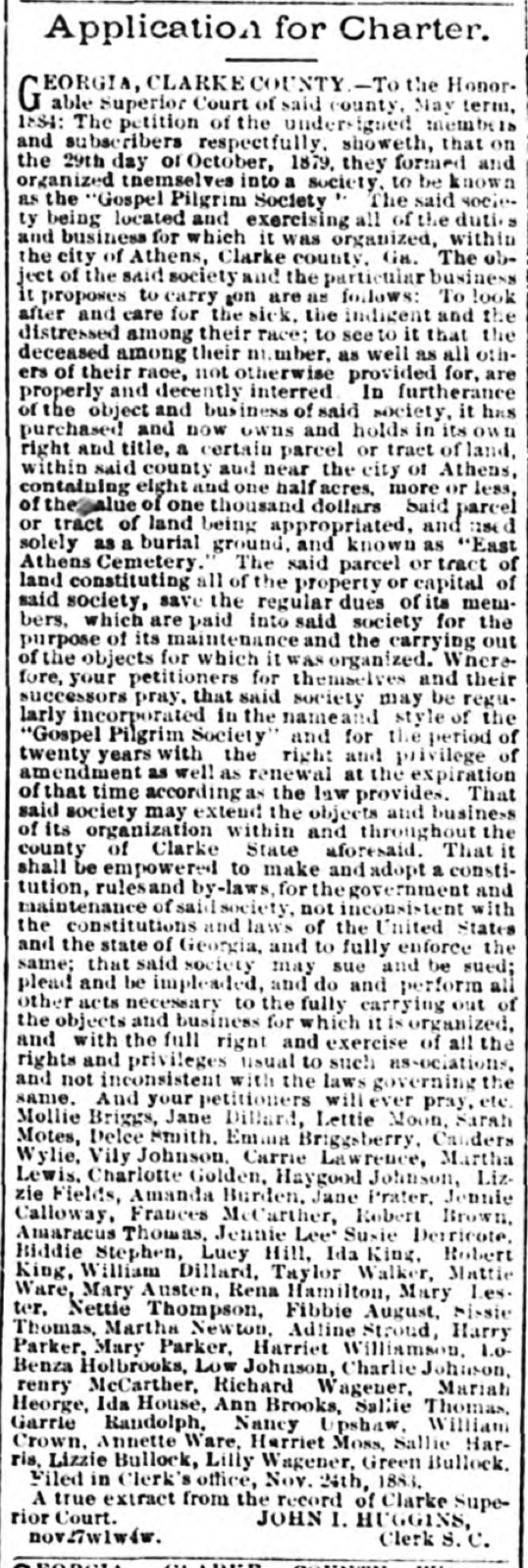

In 1879, the Gospel Pilgrim Society, a black benevolent organization, formed in Athens and, three years later, in 1882, this “Colored Lodge” came together to address a vital community need. [16] “The objective of the said society and the particular business it proposes to carry on are as follows: To look after and care for the sick, the indigent, and the destressed among their race; to see to it that that deceased among their number, as well as all others of their race, not otherwise provided for, are properly and decently interred.” [17] To achieve that end, the lodge acquired a building on the corner of West Hancock Avenue and Pope Street and a large plot of land, to be “used solely as a burial ground and known as ‘East Athens Cemetery.’” [18] The property was acquired through three separate deeds over the course of three decades. The largest section, 8.25 acres, was bought on July 25, 1882 from Elizabeth A. Talmadge for $238.50 or $268.50. [19] Originally this plot of land had belonged to the estate of William P. Talmadge, a white blacksmith who owned considerable property in the Athens area; the motivations behind this sale are unclear. Then, on June 24, 1902, the society obtained a contiguous three-quarters acre from George P. Brightwell. Finally, on June 3, 1905, the Gospel Pilgrim Society transferred a one-hundred-feet by sixty-feet parcel of land, adjacent to Fourth Street, to the Springfield Baptist Church. [20]

Such benevolent societies were not uncommon among African-American communities in the post-Civil War South. While such organizations had existed during the antebellum era among free blacks in the northeast and urban South, fraternal lodges “quickly gained widespread appeal among freed slaves after the Civil War, when African Americans realized that white society was not going to assist them in times of financial crisis, sickness, or death.” [21] Some offered health insurance, but many, like the Gospel Pilgrim Society, specialized in providing burial services and funeral plots. [22] Membership in mutual aid societies reached its peak during the 1880s and 1890s. [23] In Athens, by 1919, there were twenty-nine lodges with approximately 2,500 members, “or about 75 percent of the adult black population of Athens.” [24] Particularly popular among the South’s impoverished, “burial insurance is usually the first to be taken out and the last to be relinquished when times grow hard. It is considered more important by the very poor than sickness or accident insurance. . . No Negro. . . can live content unless he is assured a fine funeral when he dies.” [25] Black Athenians valued the services provided by the Gospel Pilgrim Society. On August 3, 1926, fifty-two years-old Lewis Lester died suddenly of apoplexy. His widow, Julia Lester, publicly expressed her appreciation to “the many friends and organizations that contributed to the fund to help bury her husband.” [26]

And many Black Athenians were buried at Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. The “spatial segregation of the American dead was the rule” in the era before municipal or commercial burial places. [27] Athens was no exception. Oconee Hill, a Victorian-style garden cemetery located near the University of Georgia’s campus, had segregated sections for whites, Jews, and blacks. It, however, catered primarily to white southerners and the African-American section, placed in the least desirable part of the cemetery, was outside the perpetual care section. [28] Gospel Pilgrim, then, served an important role in the community. As one of the first black owned and operated cemeteries in the area, it gave former slaves and freed people a space of their own in the Jim Crow South. It gave them a place to mourn their loved ones and bury their dead, as they saw fit. The enslaved had but little choice where to bury their dead. As one historian notes, “even if the landowners gave them permission to select the location for their graveyards, there would certainly have been limitations on which spot they selected; most owners would have balked at having African Americans buried adjacent to their own houses or gardens.” [29] But, after 1882, there was, at least, some choice for black Athenians. Even sharecroppers or others too poor to own private property could join the Gospel Pilgrim Society, ensuing a proper burial and a plot of land.

Over the course of its one-hundred-and twenty-one-year history (1882-2003), approximately 3,500 African Americans were buried in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery (approximately twenty to twenty-five percent of those were formerly enslaved individuals). [30] Most were interred during the cemetery’s heyday in the 1930s and 1940s and, in those decades, funerals were a common sight in the cemetery. [31] In the South, most African-American funerals commenced by cleaning and laying out the dead. It was a family and a community affair. The wake or funeral, often held at the home of the deceased, “provided an opportunity for socializing and feasting, often with culturally specific foods.” [32] At times, there was a striking contrast between the poverty experienced by the deceased in life and the opulence experienced in death as black families poured their resources into providing a handsome hearse, a well-made coffin, and abundant floral arrangements. “In the African-American community,” Lynn Rainville notes, “the funeral may have provided a chance to confer on the deceased a social dignity that was often lacking in life.” [33] Then came the burial, which conveyed “an ‘atmosphere of weeping,’ with an emphasis on emotional responses.” [34] The Brown Family, of Athens, presumably followed such customs after losing their baby to pneumonia in 1913. Having most likely cleaned and dressed the infant, A. S. Brown and his wife held a private funeral at their home before laying their infant to rest at Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery at three-thirty in the afternoon. [35]

While atypical, some black funerals had interracial attendees and the burial of Mahalie McQueen in 1910 was one such exception. Known as the woman who “Made Clothes for Three Wars,” Mahalie had sewn uniforms for soldiers involved in the 1840s Indian Wars, the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. [36] At ninety-eight-years-old, she died at her “cottage home” on Hull Street. At three o’clock on the afternoon of March 23 a service was held at Pierce’s Chapel A.M.E. Church. The burial, at Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, followed. In attendance were “many white friends of the aged and respectable colored [friends] of the aged.” [37] Evoking the spirit of the Lost Cause, a white newspaper remembered her as “a faithful servant and the loyal friend of so many who knew her when she was one of the class which made the old Dixie a nation, the like of which the world will never see again.” [38] She had been born the property the Hill family. She, as an enslaved woman, had helped raised David C. Barrow Jr., the University of Georgia’s Chancellor from 1906 until 1925. Only in 1865 did Mahalie obtain legal freedom and, even then, it was an incomplete freedom in the segregated South. We can only speculate about the precise nature of the relationship between the deceased black woman and the white onlookers. But one thing is certain: they were not equals in the eyes of the law or society. [39]

Once interred in the cemetery, families assumed the long-term task of caring for the plot—clearing leaves, clipping grass, trimming bushes, and, generally, waging a war against nature’s encroachment. Family members often visited the cemetery to commemorate birthdays, anniversaries, or other special occasions; “families, including children, would visit the site not only to spend time at the grave, but also to clean the plot.” [40] This custom survived well into the twentieth century. Reverend Archibald Killian had fond memories of Gospel Pilgrim from his childhood. “After church services, a crowd would gather at the cemetery to lay a community member to rest. Once that was accomplished, parents would take their children around the cemetery to show them where their own ancestors were buried,” he recalled during a 2003 interview. [41]

But time passes, and family scatters. The exodus of southern blacks over the course of the twentieth century left some plots without a caretaker. While separated by vast physical distance, the deceased mattered to these families and some went to considerable trouble and expense to maintain their family plots. Salemma Green died in 1944. Her daughter, Ellen Green, left Athens to take a deanship at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. [42] “Ellen sent me instructions to keep the family plot cleaned and maintained,” recalled Leo Barnett, an Athens-area resident known for performing cemetery maintenance. [43] In 1977, Ellen died in Nashville. She was interred, in Athens, near her mother and brother, Augustus, a Sergeant Major who had preceded her in death in 1941. [44]

Gradually the cemetery fell into disarray and, after 1960, fewer and fewer people were laid to rest within its geographic bounds. Problems compounded during the 1970s. In 1973, a tornado, “bouncing like a rubber ball,” passed through East Athens, toppling trees and gravestones in its wake. [45] Alfred Hill, the last surviving member of the Gospel Pilgrim Society, died of a heart attack in 1977. “Alfred Hill was well throught-of. He was an intelligent man and sold lots in the cemetery. . . . [He] worked right up until he had a heart attack,” recalled an Athens resident in 2003. [46] His death marked the end of an era. There had been no long-term arrangement made for perpetual care; families, with members still living nearby, did they best they could to maintain their own plots. But nature reclaimed the landscape. By the early 2000s, the cemetery appeared as an overgrown wooded lot. [47] One of the cemetery’s last burials occurred in November 2003; Cleo Johnson was buried beside her husband, Curtis Johnson, in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. [48]

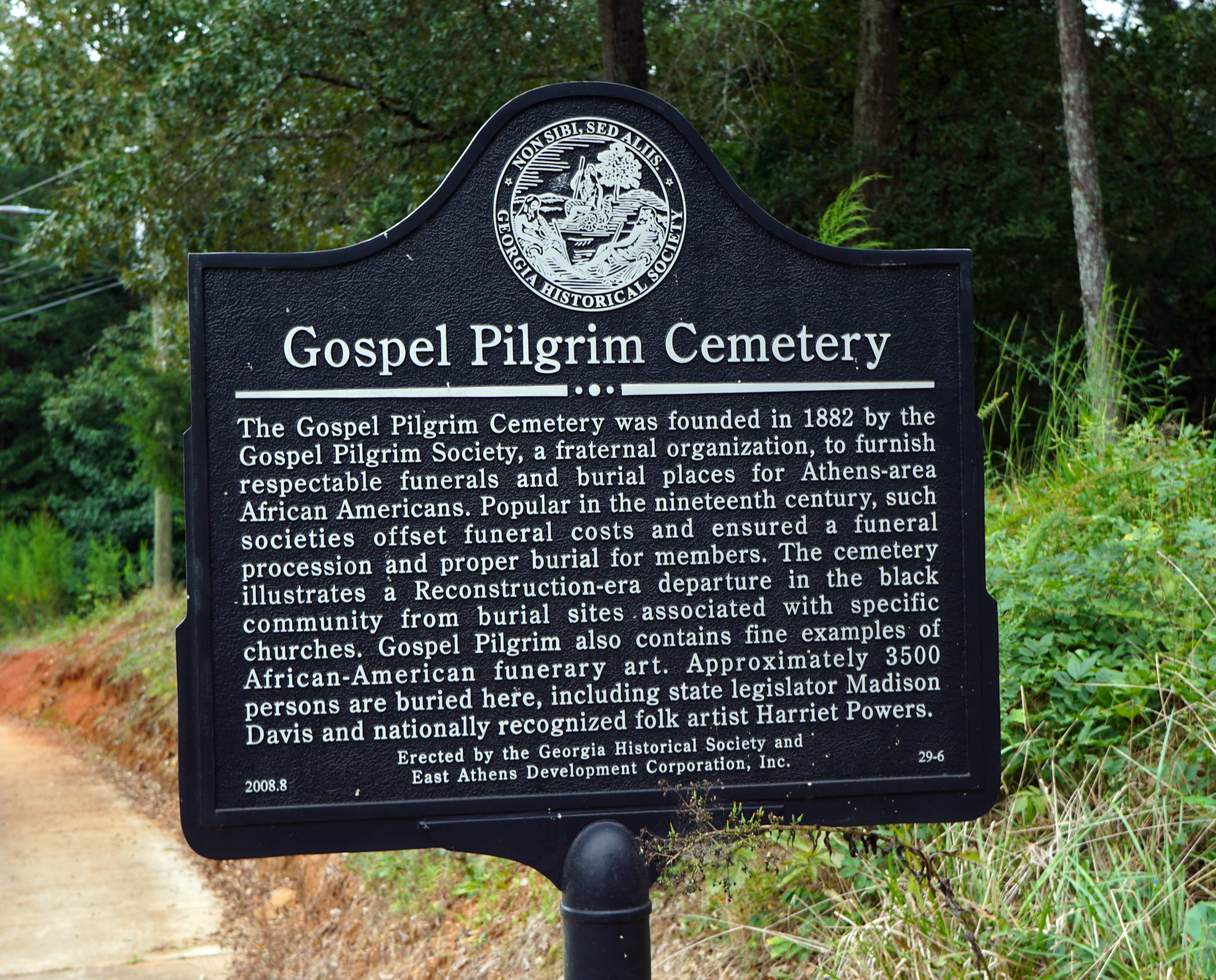

Then, in the early 2000s, the white and black community came together again. This time to apply for a historical maker; the cemetery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in April 2006. Two years later, in 2008, the Georgia Historical Society, in conjunction with the East Athens Development Corporation Inc., erected a state historical marker on Fourth Street. It reads: “The Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery was founded in 1882 by the Gospel Pilgrim Society, a fraternal organization, to furnish respectable funerals and burial places for Athens-area African Americans. Popular in the nineteenth century, such societies offset funeral costs and ensured a funeral procession and proper burial for members. The cemetery illustrates a Reconstruction-era departure in the black community from burial sites associated with specific churches. Gospel Pilgrim also contains fine examples of African-American funerary art. Approximately 3,500 persons are buried here, including state legislator Madison Davis and nationally recognized folk artist Harriet Powers.” [49] Then, in the mid 2000s, the Southeastern Archaeology Service began the painstaking process of finding and counting the dead using GIS locations. While a crucial first step, more work remains to be done.

Today

This overgrown landscape was once the centerpiece of a vibrant community. It was a space created by and for black Athenians. It had, and indeed still has, profound meaning and importance for the surrounding community. It is, as one local historian notes, a “space for quiet times with friends and loved ones, both those still with us and those gone ahead; space to discuss our lives; and space to simply remember.”[50]

Here, at The Athens Death Project, we seek to remember and rehabilitate this space as well as reckon with lasting legacies of slavery and the racial inequalities of Death in the American South. Our project takes two forms. First, the University of Georgia’s Franklin Residential College, in conjunction with the Friends of Gospel Pilgrim, promotes service-learning days aimed at restoring and maintaining the cemetery grounds. Second, this project maps the locations of graves (marked and unmarked), datafies historical death records, collects demographical data, and, from those sources, extrapolates the lives of black Athenians, both free and formerly enslaved. By assuming a digital form, we make these narratives, sources, and data visualizations publicly accessible to local residents, genealogists, and scholars across the globe.

This project, however, is about community. The black community built this cemetery. And, so too, is this a collective, community endeavor to reconstruct the lives and deaths of those buried at Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. We invite users to contribute photos, documents, leads, details, and memories of the approximately 3,500 individuals who call this space their final resting place. Please contact us.

[1] Maxine Pinson Easom and Patsy Hawkins Arnold, Across the River: The People, Places, and Culture of East Athens (Athens, GA: 420 Millstone Circle, 2019), 358.

[2] A photo of this gravestone, taken prior to 2007, is included in Emmeline E. E. Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress: Rehabilitating an African American Cemetery for the Public,” M.A. Thesis, University of Georgia, 2007, 92.

[3] A photo of this gravestone, taken prior to 2007, is included in Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 92.

[4] Gail T. Tarver, “2007 Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery Inventory,” (February 12, 2008).

[5] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 45.

[6] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 21.

[7] A photo of the felt stars, taken prior to 2007, is included in Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 88.

[8] In 2007, conch shells were found at approximately thirty graves. Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 21-22, 57, 70.

[9] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 110; Rachel Malcom-Woods, “Cheering the Ancestors Home: African Ideograms in African-American Cemeteries,” The Folk Art Messenger, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring/Summer 2004.

[10] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 21-22.

[11] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 34.

[12] William Faulkner, Go Down, Moses (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011), 128.

[13] Al Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery: An African-American Historic Site (Athens, GA: Green Berry Press, 2004), 33.

[14] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 65.

[15] Al Hester, "Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery: A Rich Resource in African-American History," Athens Historian, Athens Historical Society (Fall 2004), 42

[16] Another newspaper article dates the founding of the Gospel Pilgrim Society to 1873. Regardless, this organization came into being in the 1870s. The Banner-Herald (Athens, Georgia), September 12, 1926.

[17] The Banner-Watchman (Athens, Georgia), December 18, 1883.

[18] The Banner-Herald (Athens, Georgia), September 12, 1926; The Banner-Watchman (Athens, Georgia), January 1, 1884.

[19] Other sources list the sale price as $268.50; according to secondary sources, the document is not entirely legible. Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 14.

[20] Morris, “Gospel Pilgrim’s Progress,” 63-64; Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery Council, "General Information Packet for Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery," 1938/2009, Digitial Library of Georgia http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/do:arl_gpc_gpc072 (accessed September 19, 2019), 6-7; Easom and Arnold, Across the River, 263.

[21] Suzanne E. Smith, To Serve the Living (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 40.

[22] Smith, To Serve the Living, 40.

[23] Smith, To Serve the Living, 41.

[24] Michael L. Thurmond, A Story Untold: Black Men & Woman in Athens History (Athens, GA: Deeds Publishing, 2019), 48-49.

[25] Smith, To Serve the Living, 41-42.

[26] The Banner-Herald (Athens, Georgia), September 12, 1926; Death Certificates, Vital Records, Public Health, RG 26-5-95, Georgia Archives (Marrow, Georgia).

[27] Wilbur Zelinsky, The Enigma of Ethnicity: Another American Dilemma (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001), 76.

[28] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 11.

[29] Lynn Rainville, Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014), 65.

[30] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 11.

[31] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 11, 20.

[32] Rainville, Hidden History, 67.

[33] Rainville, Hidden History, 69.

[34] Rainville, Hidden History, 70.

[35] The Athens Banner (Athens, Georgia), February 28, 1913.

[36] The Athens Banner (Athens, Georgia), March 23, 1910.

[37] The Athens Banner (Athens, Georgia), March 23, 1910.

[38] The Athens Banner (Athens, Georgia), March 23, 1910.

[39] The Athens Banner (Athens, Georgia), March 23, 1910.

[40] Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery Council, "General Information Packet for Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery," 1938/2009, Digital Library of Georgia http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/do:arl_gpc_gpc072 (accessed September 19, 2019), 17.

[41] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 29.

[42] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 23.

[43] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 23.

[44] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 23.

[45] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 31; The Red and Black (Athens, Georgia), April 3, 1973.

[46] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 25.

[47] Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery Council, "General Information Packet for Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery," 1938/2009, Digital Library of Georgia http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/do:arl_gpc_gpc072 (accessed September 19, 2019), 12-13; Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 31.

[48] Hester, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, 25.

[49] Georgia Historical Marker, “Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery,” 2008.8, 29-6.

[50] Easom and Arnold, Across the River, 356.