Sam McQueen

Born in 1848, Sam McQueen is emblematic of an upwardly mobile and economically prosperous African-American middle class that emerged after the Civil War. In particular, Sam’s barbershop typified the continued deference towards white society that African-American entrepreneurs needed to perpetuate in order to make a living. Their wealth, however, funded important projects and initiatives that supported the independence of their communities (Mills 18, 21). Both Sam and his mother, Mahala McQueen, moved between African American and white societies, having extensive obituaries and mentions in Athenian newspapers throughout their lifetime. The following article examines Sam’s life and the network of people he impacted – the barbers he employed and the extensive McQueen clan. This article represents a partial snapshot into his life, and we hope that more about him and his family continue to emerge from the historical record.

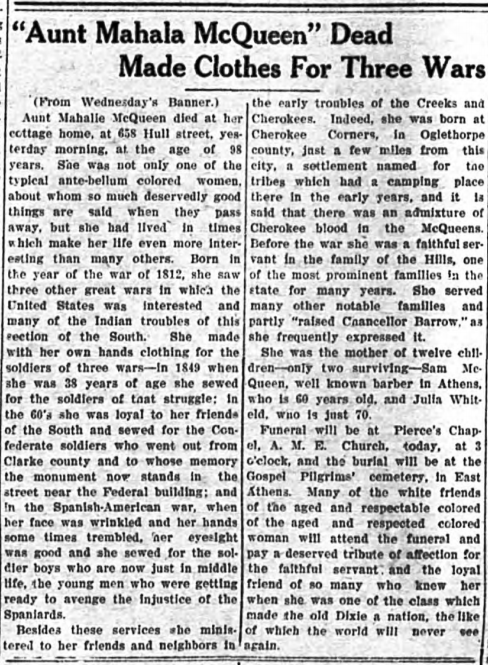

Mahala McQueen (née Wooden) survived four wars throughout her lifetime, including the War of 1812 at the time of her birth. She later sewed and mended clothes for soldiers in the Mexican American War, Civil War, and the Spanish American War. Born at Cherokee Corners in Oglethorpe County, she was rumored to have Cherokee ancestry and supposedly witnessed numerous conflicts between the Creeks and Cherokee. Despite these rumors, Sam’s certificate does not list Cherokee under his racial category. In addition to her enslavement with the Hill family, her obituary notes her labor for the Barrow family in raising David Crenshaw Barrow, former University of Georgia Chancellor from 1906 to 1925. At the time of her death, she birthed twelve children with only two surviving, Sam (60) and a daughter, Julia Witheld (70). Sam’s obituary, however, notes that he has a brother, Mat, who “was also a trusted servant of the white people of Athens” and worked for the express company ("Sam McQueen Dead”). Mahala passed away at 98 years old in her cottage home at 658 Hull Street on March 22nd, 1910. Her obituary described her as “one of the class which made the old Dixie a nation, the like of which the world will never see again” (“Aunt Mahala McQueen’ Dead”).

The earliest mention of a McQueen barbershop occurs in a Banner Watchman advertisement dated September 2nd, 1885 ("Local Clips”). It is unclear whether this shop which was operated alongside a Durham and later a Carter, as stated by an 1898 advertisement, refers to Sam’s business. A 1908 review fails to mention any business partner and instead highlights his relationship to his former master, Alonzo Franklin Hill. Sam accompanied Hill during his as a Captain in the Confederate Army. McQueen’s duties included acting as Hill’s personal bodyguard and manservant while stationed in Virginia for a year. His close relationship with Hill carried over into the creation of his barbershop, providing an important marketing tool to gain a white customer base. In particular, the 1908 review notes that he includes a painting of his former master on the walls that belonged to his mother. Put in a “handsome frame,” the article says that the painting was “one of his most “precious possessions, having been in the possession of his family for over forty years” ("His Master’s Memory”). Sam’s connection to Hill represents a common trend among Reconstruction African American barbers in the still racialized South. Many former slaves turned businessmen utilized their connections to affluent white families to gain support and economic prosperity. As a result, barbers needed to balance the politics of both communities – seeking equality for their own communities while also maintaining certain racial stereotypes (Bristol 77, 85).

The proximity of Sam’s shop to the Commercial Hotel further ensured a white customer base by positioning his services as expensive and luxurious. An earlier 1895 review highlights the cleanliness of his shop and locates his shop’s success “to the fact that it is always neat and clean.” Additionally, they describe the shop as “first class in every respect” ("A Clean and Neat Shop”). Sam’s barbershop illustrates how service trades such as domestic work, cooking, and hairdressing became viable economic opportunities for freed slaves. White society viewed these professions as connected to the roles that slaves enacted before the Civil War (Bristol 77). The racial legacy of service to white society further meant that many of these businesses catered only to white communities by providing elite and luxurious services situated near hotels. Consequently, Sam used his connection to a prominent Athenian family to secure a permanent source of revenue which his shop’s location bolstered.

African-American barbers also took on leadership roles within their communities due to their financial standing and relationships with white society. Sam exemplifies this leadership role as he contributed to numerous outreach programs and served on two Federal Grand Juries as the only juror of color in 1907 and 1914 (“District Court Convenes”). The Athens Banner notes Sam’s attendance at a meeting of African American ministers and community leaders on April 11th, 1917. Meeting to discuss the potential food scarcity during the approaching summer, McQueen and other leaders agreed to create a patriotic parade and mass meeting to discuss “raising food crops, making gardens, producing dairy and meat products” ("Colored People in Line for Patriotism”). His philanthropy indicates that barbers utilized their wealth to further their community’s advancement while also protecting their own interests (Bristol 128).

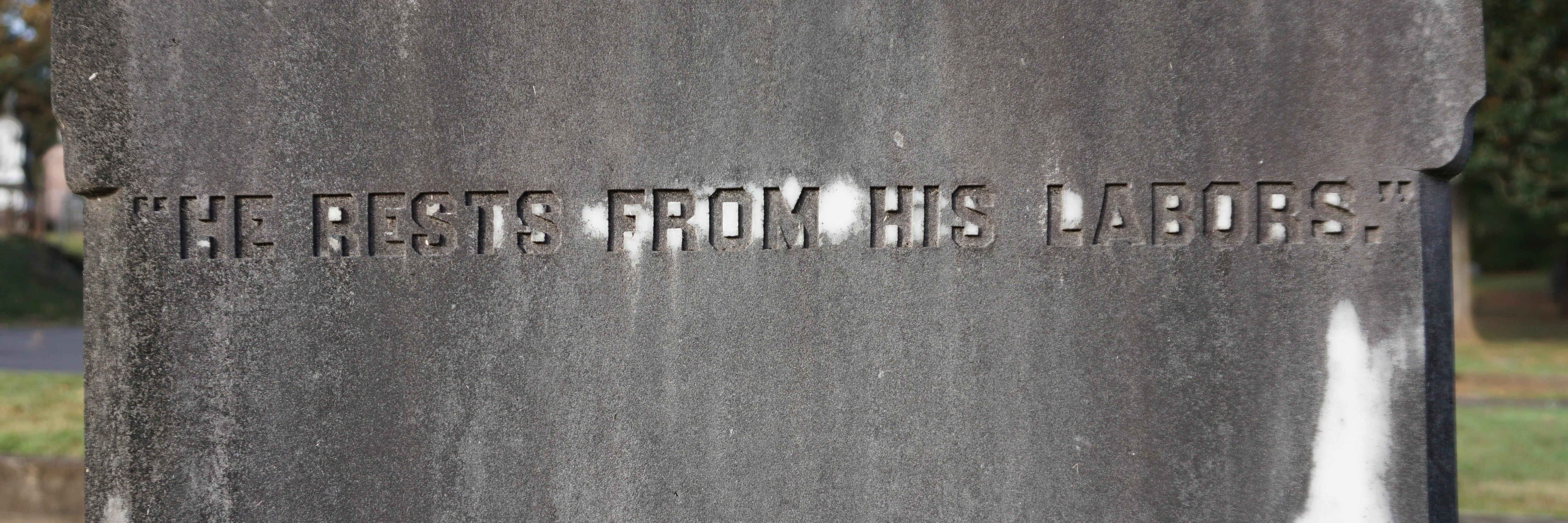

Sam passed away at 72 years old in his 656 Hull Street home of nephritis, or inflammation of the kidneys, on December 26, 1921. His obituary states that “In the death of Sam [...] the negro race lost two exemplary characters, and many people here will learn of the most recent death with renewed regret” ("Sam McQueen Dead”).

Credits

Madison Britt, Sally Smith, and John Flowers.

"A Clean and Neat Shop: Sam McQueen is the Best Barber in the Classic City." The Weekly Banner, 13 December 1895, p. 8.

"Colored People in Line for Patriotism." The Athens Banner, 11 April 1917, p. 5.

"District Court Convenes Monday, Officials Here." The Athens Daily Herald, 11 April 1914, p. 1.

"His Master’s Memory Still Lives With Him." The Weekly Banner, 10 July 1908, p. 7.

"Local Clips." The Banner Watchman, 2 September 1885, p. 1.

"Sam McQueen Dead." The Athens Banner, 28 December 1921, p. 5.

"The Federal Court is Now in Session." The Weekly Banner, 8 November 1907, p. 1.

“Aunt Mahala McQueen’ Dead, Made Clothes for Three Wars." The Athens Banner, 23 March 1910, p. 1.

Bristol Jr., Douglas W. "Regional Identity, Black Barbers and the African American Tradition of Entrepreneurialism." Southern Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 2, 2006, pp. 74-96.

Mills, Quincy T. Cutting along the Color Line : Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Thurmond, Michael L. A Story Untold: Black Men and Women in Athens History. Clarke County School District, 1978.