History of Oconee Hill Cemetery

History

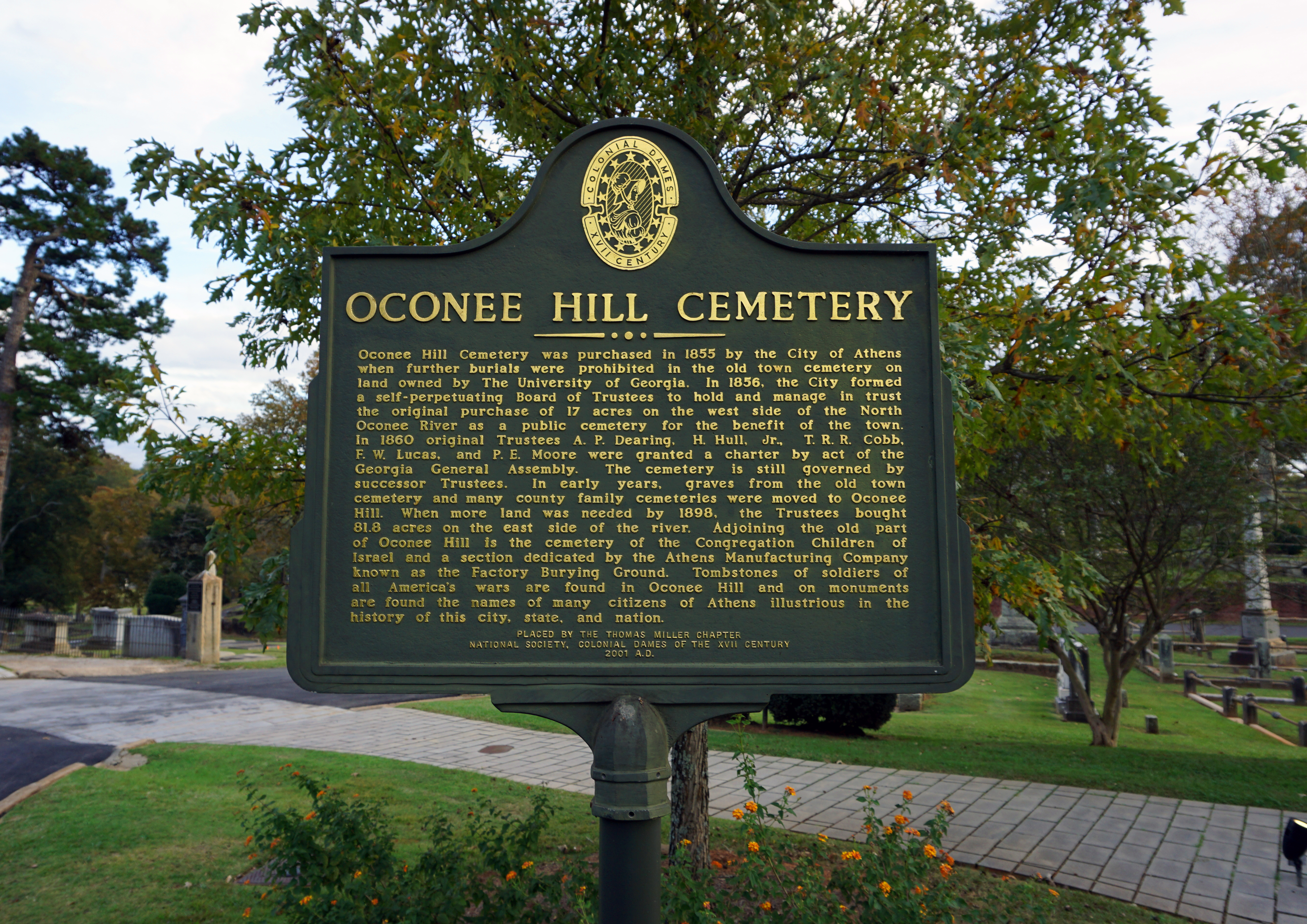

Oconee Hill Cemetery is a historic cemetery that was needed when space was no longer available at the existing cemetery. A board of trustees quickly took over the upkeep of the new cemetery and quickly began selling off the new lots. They appointed a Sexton to dig graves and look after the grounds but the position’s only income came from digging graves, but a salary was later set into place after a period with very few new arrivals for the cemetery. The cemetery has seen a lot of construction since its opening including a railroad that was placed right next to it and a bridge that connected the existing land with the new expansion for the cemetery that was purchased. Oconee Hill Cemetery is a historic cemetery that has seen its own share of history since it has opened.

Jackson Street Cemetery became overcrowded so in 1854 town wardens began looking for a new cemetery grounds. On March 1, 1855 the committee found a 17 acre lot near Oconee River, and bought it from Pamela A. Hopping for $1,000. A portion of the land was set aside for African Americans in the original charter printed on January 8, 1857 in the Southern Watchmen’s “article Oconee Hill Cemetery. Head and foot stones were allowed for them but the designated space didn’t have an enclosure. As for the Paupers section, the charter claims that the city council will make the necessary payments for their plots. The charter also stated the fees of the Sexton. Digging a new grave cost $5 but removing someone from one grave and moving them to a new one cost $10.

The cemetery opened to the public in 1856. The original land consisted of the current West and East Hill portions of the cemetery. Plots at this time were sold at public auction. The land itself was designed from a plan by Dr. James Camak. The plan’s design was based on the Victorian cemetery movement.

Interestingly, there are many graves in the cemetery that were buried before the opening of the cemetery. These graves were moved from the Old Athens Cemetery upon its reduction in size. Old Athens Cemetery was originally around 6 acres in land but is now much less, so many of the graves were moved from their original location to Oconee Hills Cemetery. However, the interesting thing is that some graves actually remain in Old Athens Cemetery, but their headstones or markers were moved to Oconee Hill.

In addition, Oconee Hill has always been a cemetery that is extremely inclusive to all races and ethnicities that would want to be buried there, but this isn’t exactly evident from all outward appearances from the Cemetery itself. While African-Americans were allowed to be buried at the Cemetery, unfortunately it was these members of Athens society that were the poorest, and thus they couldn’t afford a lavish headstone or grave marker for their loved ones. Today, much of the African-American section of the cemetery is unmarked and overgrown, and it isn’t exactly evident that bodies are buried there.

The Trustees started employing a Sexton to take care of the grounds in 1857. The Sexton was in charge of all interments. In 1896, there were some complaints about Sexton England. Citizens were upset that he was not having the graves dug in time for interment. The Trustees called a meeting to decide how to prevent other Sextons from not performing the job properly. The Trustees came to conclude, that an election for Sexton would take place every December. Sexton England was to keep his job until December, and come up in the votes with other potential candidates. In the following December, J.C. Mygatt was elected as the new Sexton of Oconee Hill Cemetery. Within a month of the job Mygatt resigned and the board appointed J.H. Bisson. Towards the end of his first year as Sexton, a citizen wrote a letter to the editor of the Athens Banner applauding Bisson for a wonderful job taking care of the cemetery. The citizen also said that the city should start paying the Sexton a salary. At that time, the Sexton was only paid a small amount for digging graves and taking care of a few grave plots. That next year Bisson requested a salary from the city, for he had only made seven dollars in a six months. The Athens Banner stated, “The City Council should grant it without hesitation.”

In 1897, the city gave police powers to the sexton, to be able to properly protect the cemetery against vandals. In that same meeting between the city and the Trustees, an ordinance against bathing in the river at the cemetery. Along with being the Sexton Bisson ran a granite plant, which was located at the entrance of the cemetery. To make the appearance of the entrance more attractive, they moved the granite plant in 1906. The fight for the sexton to get a proper salary continued for years. From 1915 to 1917, the Trustees incorporated the cemetery. The legal document stating this would procure the Sexton with a salary.

In 1888, plans were made for the Macon and Covington Railroad to be built through Athens, connecting it with Elberton, Macon, Atlanta and the Georgia, Carolina and Northern Road. It was initially supposed to be finished in July, however controversy occurred when the railroad wanted the right of way through Athens, which would be a costly endeavor. It would also cause the railroad to cut through part of the Oconee Hill cemetery. This threat came at a time when initial building for the road was already underway. A bridge was built across the Oconee river by the factory and the lower edge of the Oconee Hill cemetery was already “disfigured by a steep embankment while the street leading to our city of the dead is rendered impassable by a very deep cut”. Eventually the required money was drummed up, and the Trustees presented the right of way agreement to the Mayor and City Council. The issue was finally settled and the road was built, blocking the entrance and destroying parts of the African American burial grounds. The next railroad related controversy was over how the building of the road blocked the entrance to the cemetery, and the city compelled the Covington and Macon Railroad Company to build a wooden bridge on Cemetery street, which was completed in 1891. The land around the tracks was bought in 1930 and 1939 by the cemetery in attempts to beauty the cemetery. The wooden bridge remained until the 1960s, when a new road was built from East Campus Drive, connecting to the entrance of the cemetery. Before becoming non-operational, the railroad was owned by the Central of Georgia, one of the largest rail companies in the state.

The Oconee Hill Cemetery was originally run by the city but it was later run by a board of trustees who were responsible for its care and upkeep independent from the city. These trustees were Frederick W. Lucas, Henry Hull, Thomas R. R. Cobb, Albin P. Dearing, and Peyton F. Moore. They also appointed a Sexton to dig graves and to maintain upkeep on the grounds. Originally his only payment came from digging new graves and moving people from one grave to another. After a six month period where only fifteen people were buried in the cemetery, a petition was made by the Sexton to give him a small salary. He claimed “there is no living in Athens in burying the dead” in the article “A Worthy Petition” published in Athens Daily Bannerin the June 9, 1898 edition.

The cemetery started to fill up in the 1890s to the point where expansion became necessary. In 1897, a recommendation was made by the trustees of Oconee Hill Cemetery to the city to purchase additional land for the cemetery. According to the Weekly Banner’s article “Will Discuss It” one of the trustees, Mr. Lucas, made their case by claiming that there was no ideal looking plot left to sell and more land was necessary. Judge Cobb, another trustee, claimed that the city should purchase the land because even though the land is supposed to cared for by the trustees, it still belonged to the city. The 25 acres of land in question, across the river by the cemetery, belonged to a Mr. Thomas Balley and they estimated the value of the land to be around a thousand dollars. There would also be the cost of the bridge that would have to be built to gain access to the land, and that was estimated to cost around $1,600, which was not even close to the actual cost of building the bridge. They also made two additional requests at the meeting, the first of which was that it be illegal to bath in the river. The second was to give the sexton police power over the cemetery. Both the sexton’s power and the river ordnance were granted by the council, as well as the purchase of land, but the bridge had to be at least partly paid by the trustees of the cemetery.

The bridge was built in the year 1899 along with the expansion that was added on to the cemetery. According to the Weekly Banner’s article “The New Bridge Over the Oconee” the founders made a deal with the Desmoines, Iowa Company to have the bridge constructed by the 18th of July 1899. The actual cost of this bridge was about $2,600, the trustees paid $1,000 of it and the city paid the remaining $1,600. Construction in the cemetery didn’t stop with the completion of the bridge though. After it was finished, the new 25 acres that were added to the cemetery had to have walks made and space cleared for future plots, but the lots were being sold as soon as the bridge was completed.

Oconee Hill Cemetery has been around for about sixty years. It grown in size significantly since its original opening in 1856, holding thousands of people, not all of whom have grave markers, and still sells plots even today. It has seen several moments of construction ranging from a bridge during its expansion to a railroad that ran right next to it. Oconee Hill Cemetery holds historic people, historic monuments, and has been present for its fair share history since its existence.

Today

Oconee Hill’s age is part of what makes it so beautiful. The rich history that has built up since 1856 adds life to the unique cemetery. Some parts of it will inevitably need restoration though, and this needs to be done in the least invasive way as possible. Certain stones and grave markings must be repaired if descendants ask for such. The processes of restoring gravesites is very tedious, so it only should be done when agreed upon between the Friends of Oconee Hill and the family of the deceased. The roads also are in need of a restoration. In order to accommodate all ages of people wanting to walk throughout the cemetery, the walkways must be ridden of cracks and potholes. Finally, the area near the river also needs to be reinforced. Currently, many of the gravesites are in danger of being washed out during floods. A barricade along the river would suffice and could also add to the appearance of the site if designed correctly.

What to do with certain sections

In June 2013, Oconee Hill was added to the National Register of Historic Places with “state level” significance, a designation which allows for tax credits and qualifies the cemetery to receive special federal grants. These grants are important to affording maintenance of the site—the Friends of the cemetery only have net funds of around $140,000—and in April 2016, they received their first grant of $10,710 to manage trees in the cemetery and reduce invasive species. According to a 2014 study of the cemetery by the Chicora Foundation, Inc., the continuity of the grounds hinges on treating the area as a business and clarifying the relationship between the trustees and the city for upkeep. In terms of the specific sections of the cemetery, their future depends on who is left to advocate for them. In the case of the Jewish section which is maintained by the synagogue from which the intered were members, this is not an issue. For the factory section, which was started by a now defunct and bankrupt company, and the pauper sections, maintenance falls back on the trustees, and erosion and moles are an issue. The African American section is likely that with the most unknown future. Reflecting efforts in other university towns though, the future of this section will likely include some degree of tracing back the relatives of those buried. At Clemson, a marker is being placed at a nearby cemetery to commemorate slaves linked to the university, and at Georgetown, a massive effort is underway to trace families of 272 slaves sold to maintain the university’s liquidity. For Oconee Hill, similar care to the African American section would require greater involvement from the university and recognition of its ties to UGA, including the fact that the cemetery was designed by a UGA professor and houses university presidents.

Improving Accessibility

Oconee Hill Cemetery is placed between the Carr’s Hill neighborhood and the University of Georgia campus, laying in the shadow of Sanford Stadium. It is has two entrances with the western one located on East Campus Road with no protected pedestrian access, the other entrance at the end of Carr Street is permanently closed, likely to reduce the chances of deterioration and vandalism by removing it as a potential thoroughfare for automobile traffic between US 78 and the heart of campus. While preserving the monuments, the complete lack of traffic is also a missed opportunity for the community to enjoy the cemetery’s function as a beautiful park. Improved pedestrian access can be created in many ways. First, by means of a crosswalk leading to the cemetery from the sidewalk on the campus side of East Campus Road would promote involvement from the university community by decreasing the risk of crossing through busy traffic. A partnership between the cemetery and Athens-Clarke Leisure Services would open the cemetery up further to the community if the city had the ability to expand the North Oconee Greenway along the river to the cemetery.

Alternative Uses for Oconee Hill Cemetery

The opportunities for alternative uses of a cemetery are seemingly endless, though one must consider the interred and what is perceived as respectful. Oconee Hill Cemetery is centrally located near the University of Georgia’s campus as well as downtown Athens which, combined with its sprawl and proximity to the river, make the cemetery easily accessible to tourists and others. The Sexton’s house has already been used to host a wedding, and this trend should continue while also incorporating the Wingfield Chapel located just beyond the recently restored bridge. Advertising this unique event option on social media as well as travel magazines would place the cemetery in front of alternative and “destination wedding” couples. In addition to weddings, the cemetery could participate in events that already take place annually in Athens such as Twilight bike races and a 5K run that takes place the morning of Twilight. Obviously, the entire cemetery could not be utilized for the run, but the front entrance and gated rear entrance are connected by a fairly flat and straight road. For a uniquely Oconee Hill run, perhaps a Halloween 5K run that coincides with the annual Athens Wild Rumpus Halloween Parade would create a memorable experience for runners, their families, as well as those who are donning costumes and would enjoy a good spook. A barbeque gathering at the Sexton’s house following the run for people who bought tickets could serve as a fundraiser for the Friends of Oconee Hill foundation.

NEXT: Old Athens Cemetery