Death Certificates

In Georgia, statewide issuing of death certificates began in 1919. While some death records exist for earlier decades (principally materials collected by the State Board of Health from 1914 to 1919), most Athens-Clarke County death records date from the post-1919 era. Death records from 1919 to 1930 are indexed and available online at the Georgia Archives in Morrow, Georgia. Building from this dataset, The Athens Death Project has transcribed and datafied 3,405 death certificates for Athens Clarke County from the years 1919 to 1927.

We have uploaded these death certificates and, building from this data, we have created maps and data visualizations. Check out each of these resources.

Document Anatomy

Death certificates, of course, pinpoint a specific cause of death, which provides valuable data for statisticians, medical personal, and those interested in the history of medicine. But these sources reveal much more than simple medical diagnostics. Offering a lens into the individual’s life, death certificates indicate the decedent’s name, birthdate, birthplace, occupation, residential address, and familial connections -- valuable information for historians and genealogists alike.

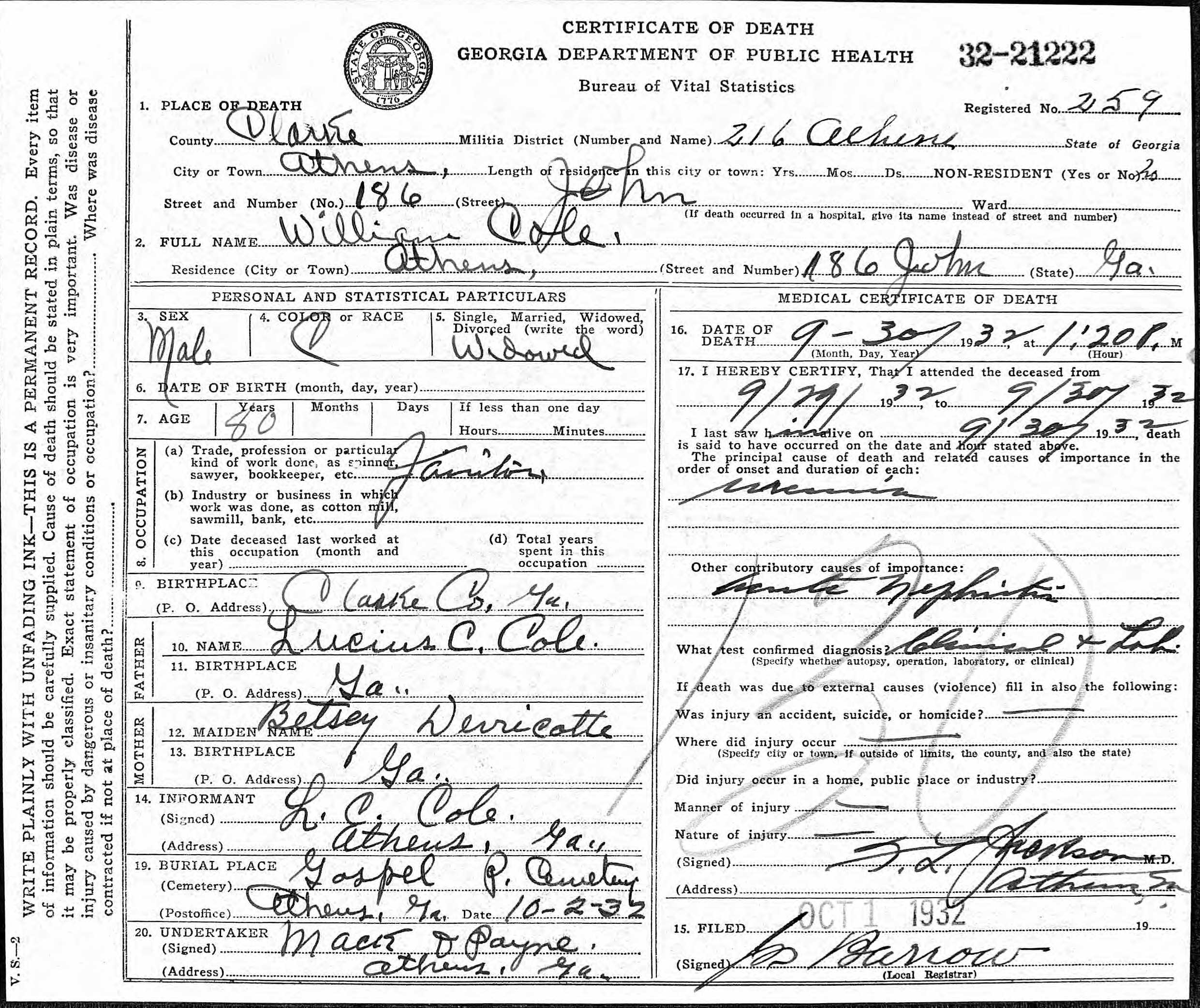

These Athens-Clarke County death certificates tend to follow a standard form: 1) Place of Death; 2) Decedent’s Name; 3) Gender; 4) Race; 5) Marital Status; 6) Date of Birth; 7) Age at Death; 8) Occupation; 9) Birthplace; 10-13) Parent’s Names and Birthplaces; 14) Informant; 15) Filling Date; 16) Date of Death; 17) Cause of Death; 19) Burial Location; and 20) Undertaker. In this case (image below), we learn that William Cole, the son of Lucius C. Cole and Betsey Derricotte, was born in the early 1850s (the date of birth is presumed based on his age at death) and most likely enslaved as a child. Later in life, he worked as a janitor and lived 186 John Street in Athens, Georgia. According to a local doctor, Cole died from uremia and acute nephritis on September 29, 1932. Under the direction of Mack & Payne Funeral Home, his body was interred in Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery. [1]

Each death certificate represents an individual life and death. On its own, each of these documents tells the miniature details of someone’s exit from this world—in that sense, it’s an archive of sad, and at times bad, endings. But it’s also a lasting record of a life lived—a record of kinship connections, of careers, of residential communities. In the case of many African Americans, it’s a testament to perseverance in an era of slavery and segregation. In some cases, the formerly enslaved enter into the historical archive and give voice to the oftentimes voiceless. By listing their parent’s names and birthplace, Black Athenians officially claimed kinship connections on official state document, despite living in a nation that consistently denied them a modicum of humanity.

And, so too, are death certificates a record of white supremacy and the violence inflicted on Black bodies. As recorded causes of death, ‘lynched,’ ‘shot by police,’ or ‘murdered’ are stark reminders of the lethal effects of white supremacy. But seemingly mundane aliments—'myocarditis,' 'nephritis,’ ‘rheumatism,’ ‘stillborn,’ ‘pellagra,’ and ‘dysentery’—can also be indicative of social, political, and financial inequality. Hard work, long hours, poverty, and limited access to health care takes a physical toll on the body. For far too many Black Athenians, “Overworked and Underpaid” could be their epitaph.

In the 1970s, epidemiologist Sherman James termed this concept the “John Henry” effect. According to the folk legend, John Henry, a Black railroad worker, fought the machine—and won. Pitched in battle against a steam-powered drill during the 1800s, Henry hammed and labored with all his might. He finished first and, in that sense, won the battle. Then, the ‘steel drivin’ man’ kneeled over dead, the ax still clutched in his hands. However embellished the legend, the point stands: physical exertion takes a toll on the body. It can kill. “The hypothesis,” according to journalist Richard Fisher, “predicts that when people face prolonged adversity – against inequality, financial hardship and racial discrimination – the ‘high-effort coping’ required to thrive will damage their health through stress. What follows is a greater likelihood of cardiovascular disease, heart attacks and other problems.” In short, “John Henryism describes the stressful, damaging health impact of thriving despite inequality, financial hardship and racial discrimination.” The concept, and its lethal effects, would have been all too familiar for impoverished Black Athenians. [2]

In the aggregate, death certificates take the pulse of a community in a particular time and place. How were residents dying? What differences emerge from the data? A statistical analysis of death certificates from 1919 to 1927, for example, indicates that white residents lived on average ten years longer than Black residents during the same era. In Athens, we have never lived equally and, in turn, we did not and still do not die equally. True social justice will be achieved when it is no longer a significant statistical advantage to belonging to one group or another when it comes to longevity, mortality, and health outcomes.

NEXT: Essays

[1] William Cole, September 29, 1932, Death Index, Georgia Department of Health and Vital Statistics (Atlanta, Georgia).

[2] Richard Fisher, "‘John Henryism’: The hidden health impact of race inequality,"BBC (23 August 2020).