Life and Labor

Our occupation does not directly predict our demise, but where we work and how we live can, in part, determine how we die. Take for example the southerner farmer: long hours spent out of doors, under the blistering sun, takes a toll on the body; heavy machinery and draft animals can easily maim a man; and chemicals designed to fertilize and enrich the soil poison the lungs and skin.

Historic census records and death certificates, however, rarely distilled employment information into consistent, precise categories. Women worked as ‘laundresses’ and ‘washerwomen’ interchangeable. Men, meanwhile, could be ‘common workers,’ ‘laborers,’ or ‘general laborers.' Regardless of their designated status, all these men worked with their hands in physically demanding jobs; today we would consider them ‘blue-collar’ workers. To facilitate analysis, we have adjusted and compressed certain occupational categories:

Categories

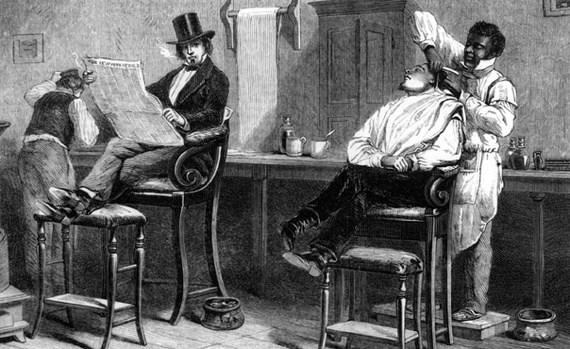

Barber --> Either owning or working in a barbershop, these men -- most of whom were African American -- styled hair and trimmed beards for either white or Black patrons. A well-respected occupation in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African-American barbers could accrue wealth or social prestige in the local community. Catering to a white clientele, Sam McQueen's barber shop, located near the Commercial Hotel in Athens, was described as “first class in every respect.” Following his death from nephritis in 1921, white southerners mourned his passing; his obituary stated: “in the death of Sam . . . the negro race lost two exemplary characters, and many people here will learn of the most recent death with renewed regret.”

Beautician --> "Hair dresser" or "Hairdresser." Catering to a female clientele base, beauticians cut and styled women's hair. Lacking the social prestige of male barbers, these women (African American and white) tended to make less than their male counterparts.

Child --> "Child" or "Infant." Infants and young children without a formal occupation. Some of these children were too young to attend school while others were of age but did not attend classes. This category contains both Black and white children in equal numbers. Felman Jordan, an African-American infant, was just twelve days old when she died suddenly at her parent's home on Macon Avenue. Many in this category are sadly similar to her: infants who died shortly after birth.

Clerk --> "Book keeper," "Dry Clerk," "Clerk in Bank," "Electric Clerk," or "Freight Clerk." Working in various businesses, clerks kept the books and processed transactions. Given the mathematical and literary skills required to succeed in this line of work, it was almost the exclusive purview of educated, white men. Born in 1859, Francis Epper recorded cotton purchases, sales, or shipments until he died from appendicitis in 1921.

Construction --> "Contract Plasterer" or "General Public Plasterer." A catch-all category for men who constructed buildings, both homes and businesses. Dave Hawkins, an African-American man, plastered homes as a contractor before his death in 1920.

Cook --> Wealthy families hired cooks to prepare and serve meals. African-American woman performing this task were poorly compensated for their physically demanding labor. As a cook, Fannie Hane would have spent hours preparing poultry and vegetables, cooking over a hot stove, and serving food. The overwhelming majority of these women were African American.

Domestic --> Hired as household workers, domestics cleaned and performed other tasks. Once again, most of these women were African American. Katherine Baldwin, Matilda Ann Eberhardt, and Mamie Louall Weatherford all preformed the backbreaking labor of scrubbing and mopping and sweeping their white clients' homes.

Drayman --> Transporting assorted goods, draymen (and, yes, they were always men) performed the physically demanding task of hauling supplies.

Farmer --> "Farmer" or "Farming." Living on the rural edges of town, white and Black families worked the land. Ramp Jones lived in the countryside surrounding Athens and worked as a "farmer" before he died from mitral stenosis in 1925. While women and children also labored in the fields, they were not typically considered "farmers" in the official sense. Thus, most individuals in the category are men. Jenni Bell was an exception; her death certificate listed her as a "Farmers Wife."

Farm Laborer --> "Farm Work" or "Farm Workers." The men (and they were almost always men) worked on farms, but do not appear to own or rent the land. Instead, they assisted a family member or were hired help.

Gardener --> "Gardener for the City," "Gardener," or "Horticulture." Working for private families or public entities (such as the city), gardeners tended to plants and performed other landscaping duties. Jefferson Tacker, an aging African-American man, lived on Hill Street and was employed as a "Gardener for the City" before his death in 1927. Peter Hutchenson also worked as a gardener before he died from pneumonia at eighty-years-old.

Housewife --> Bearing and raising children is work, and it was sometimes considered an "occupation." Prior to her death in 1920, thirty-nine-year-old Blanche Mulleken Griffeth managed her house on Dougherty Street. Rarely was a Black woman classified as a "housewife" on historic documents; in turn, few Black women appear within this category.

Housework --> "At Home" or "Housework." Again, housework is labor. It is work. The women within this category managed their own households and families. White women most often appear in this category, as African-American woman more often worked outside the home for wages.

Janitor --> Janitorial staff cleaned schools, public buildings, a local businesses. It was a physically demanding job with poor compensation, and many African-American men were relegated to this position. Elder Hicks worked as a school janitor while John Horton cleaned for the city.

Laborer --> ‘Common Workers,’ ‘Laborers,’ or ‘General Laborers.' While employed in various fields, all of these men worked with their hands in physically demanding jobs. Today we would consider them ‘blue-collar’ workers. Men of both races appear within this category, although African-American laborers on average died younger.

Laundress --> "Laundry woman," "Laundry work," and "Washwoman." In an era before in-house washers and dryers, cleaning clothing was hard work. It required gallons of boiling water and hours of scrubbing. Lucile Brooks would have used hot water to clean clothing and then, once dry, she would have loaded hot coals into a heavy, metal iron to press the fabric. Many African-American women performed this difficult job. Indeed, many white families hired out this physically demanding task. Compensation was poor, and many Black laundresses earned little.

Lawyer --> "At Law" or "Retired Lawyer." As members of the legal profession, these men worked as attorneys or judges. Educational requirements and professional contacts limited this profession to the elite members of southern society; and, as a result, only white men appear within this category. Athens area lawyers tended to live a long life, and many of these men were retired at the time of their deaths. L. B. Lightfoot, for example, was a "retired lawyer" when he died from hemiplegia and senile debility at the age of eighty-three.

Mail Carrier --> "Assistant Postmaster," "Clerk Post Office," "Rural Letter Carrier," or "Special Letter Carrier." Black and white men who worked for the postal service. Men who performed this task often earned the respect of the local community, and this profession tended to bestow an element of social prestige even for African-American mail carriers.

Mason --> "Brick Layer," "Stone Cutter," "Stone Mason," In short, men who worked with stone. All masons have been lumped into this category, regardless of their preferred medium -- brick, marble, or granite.

Merchant --> "Cotton Business," "Grocer," "Retired Merchant." Male merchants (most of whom were white), bought and sold various goods -- cotton, hardwood, groceries, and other items. Some goods were more eccentric than others; George W. Farrell sold a "Talking Mail Set." According to his death certificate, Allen Fleming's occupation was "Cotton Business" -- nowhere in this record does it specify "merchant," but we have taken the liberty of including such nondescript businessmen within this category. "Retired Merchants" are also included within this category.

Mill Employee --> "Mill Hand," "Mill Supt.," "Mill Operator," or "Mill Worker." Located in and around town, Athens boasted several textile mills, including the Whitehall Mills, and this category contains anyone who worked at a mill -- from upper management to lower-level employees. John W. Allen was a mill operator who leaved on the East Side. Women, too, worked in the mills. Ida May Strickland, for example, was a "mill hand." Workers typically lived in company owned housing nearby.

Nurse --> "Trained Nurse." Nurses cared for the sick. Twenty-six-year-old Irene Day was a "student nurse" at St. Mary's Hospital when she suffered a broken neck and crushed chest during a car accident; she died from her injuries on April 10, 1924. Most all within this category are women.

Physician --> "Doctor," "M.D.," or "Physician Surgeon." Healing patients and performing surgeries, Athens doctors worked in the local hospital or in private practice. Dr. O. L. Deadwyler worked at St. Marys Hospital. Dr. J. P. Procter, meanwhile, worked as a surgeon. Poverty and segregated school systems barred many African-American men from this profession. Women, likewise, rarely entered this field.

Porter --> "Porter Waiter," "Pulman Porter," or "Hotel Porter." Derived from the Old French word portier (meaning gatekeeper or doorkeeper), men in this occupation fetched and carried luggage or food. While born in Athens, L. B. Barnett moved to Chicago where he worked as a "Pulman porter." Another African-American man, Will Henry Graham, lived on Broad Street in Athens and found work as a "porter" for an unknown establishment. A physically demanding job with limited social prestige, many African-American men performed these essential tasks.

Professor --> "College Prof" or "Prof." Elite, educated, white men who taught at the University of Georgia. After a long-life spent teaching Greek at the University of Georgia, Joseph Lustrat died from myocarditis and pericarditis on February 3, 1927. Henry Clay White, meanwhile, was a professor of Chemistry before his death.

Railroad Employee --> "Consulting Engineer," "Locomotive Engineer," "R R Engineer," "Retired R. R. Engineer," "RwyEmployee," "Rail Road Section Foreman," or "R. R. Workman." Anyone who worked for the railroad. Alfred B. Bailey was employed as an engineer while John Nickson worked as a "R. R. Workman." Despite the various career paths and pay grades, most of these men are white. And none are women. Regardless of their assignment, railroad work was physically demanding and dangerous -- heavy metal train cars severed hands, crushed feet, and fractured skulls.

Real Estate --> Buying and selling houses. John T. Anderson worked in real estate before his death from cancer in 1927. Likewise, it was the profession of fifty-one-year-old Alonzo C. Hancock. Both Anderson and Hancock were white men. Indeed, the profession was dominated by white men, most of who attributed to racial segregation by prevent African-Americans from buying homes in particular neighborhoods.

Retired --> This category is only used when no other employment information is available. Reuben Thomas White was a retired minister; instead of categorizing him here, he is considered a "Reverend." James Francis Whittaker, on the other hand, is considered "retired" for the purpose of this study; there is no other employment information available.

Reverend --> "Clergyman," "Minister," "Pastor," and "Preacher." A man of God. Baptist, Catholic, Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Methodist, reverends worked at churches and lead their local congregations. Both Black and white men felt this calling. Before his death from nephritis in 1921, J. T. Richards worked as a "Minister of the Gospel at A.M.E. Church."

Sales --> "Salesman," "Saleslady," or "Traveling Salesman." Salesmen sold various goods, including cotton, groceries, sporting goods, and construction equipment. M. W. Cochran worked as a "wholesale grocery salesman" and Guy S. Weatherly was employed at "P & S Sporting Good Co" as salesman. Most of those working in sales were white men, but Annie Morrison and Carrie May Hunter were both employed as a "salesladies" in Athens.

Seamstress --> "Dressmaking," "Dressmaker," or "Shirt maker." Catering to female clientele, seamstresses made and altered women's clothing. Laura Neely, an African-American "shirt maker" in Atlanta, died from tuberculosis when she was twenty-one. In Athens, many African-American women worked in this profession.

Student --> "School Boy" or "School Girl." These children attended elementary or secondary school in Athens, Georgia. James Walter Wright, for example, was a seven-year-old white "school boy" when he was accidentally killed in a car accident on July 31, 1919. Typically, this refers to white children; largely denied the privilege of attending school, many Black boys and girls worked the fields or performed other menial tasks for wages.

Tailor --> "Tailor" or "Taylor" (the common misspelling). In an era before well-fitting, mass-produced clothing, tailors custom made or altered men's suiting. In the Athens dataset, both tailors -- Reese Colquitt and Courtney Thomas -- were African-American men, but white men also worked in this profession.

Teacher --> This category includes elementary and secondary school teachers of all grades and disciplines; "Music Teacher," "Country School Teacher," and "School Teacher" all fall under this broad umbrella. Over the course of her forty-year career, Minnie Davis taught several grades, including 1st and 5th, at the West Athens School. Prior to her retirement in 1926, The Banner-Herald reported: “Mrs. Minnie F. Davis, the only one of the [teacher’s] corps who was with the city schools when they began in 1886, on account of illness, will probably retire. She has served faithfully and efficiently. . . These. . . are among the most efficient teachers in the colored system.” In the South, schools were segregated during this era. The better-funded and better-equipped white schools employed white teachers; the under-funded black schools hired black teachers. Both school systems, however, employed female teachers, and many within this category are women.

Veteran --> 'Veteran' is not a commonly employed category; veteran status was only denoted as an occupation if these men did not have another form of known employment. If, for example, a man fought in the First Great War but then retuned home to work on the railroad, he would be considered a "Railroad Employee" for the purpose of this study.

Other jobs or careers fall outside of these categories. For example, W. D. Bowden worked as a "Ice Cream Dealer," John Henry Gann labored as a "watchmaker." These occupations remain as listed in census or death records; we have not attempted to distill this data into more precise categories.